Photo by Leighann Blackwood

By Seanna Leath, University of Virginia

August 15, 2019

The Ghanaian-American author Meri Nana-Ama Danquah became well-known for her memoir detailing her struggle with depression. She writes, “Mental illness that affects White men is often characterized as a sign of genius. White women who suffer from mental illness are depicted as spoiled or just plain hysterical. Black men are demonized and pathologized. Black women are certainly not seen as geniuses – or even labeled as hysterical or pathological. When a Black woman suffers from a mental disorder, we are labeled as weak. And weakness in Black women is intolerable.”

Too often, Black women struggle with expectations and responsibilities that lead them to neglect their own health and wellbeing. There is little discussion about the particular challenges Black women face, and still less done to help them meet those challenges. It should not be a surprise then, that Black women are more likely to die at a younger age than women from other racial groups. While some efforts are being made to address racial disparities in maternal mortality and breast cancer, there is an overwhelming silence about how we can improve the overall health of Black girls and women by focusing on their mental health and emotional wellbeing.

In my research, I explore Black women’s mental health. I find that educators, leaders in Black communities, and others concerned by these disparities need to learn to talk about these issues. Once these discussions are opened, my research offers a few suggestions about how to promote health and wellness among Black girls and women by focusing on family dynamics, schooling experiences, and access to community resources.

The Burden of Strength

Black women are often described as Superwomen. This is typically meant as a compliment and received positively when compared to other, blatantly negative stereotypes about Black women that cast them as sexually aggressive, lazy, loud, and ghetto. In my research interviews with young Black women, I find that many consider strength a birthright of Black womanhood. They view their survival amidst the legacies of slavery, colonialism, and disenfranchisement as a testament to the strength of Black women in U.S. society. Similarly, Black mothers are praised for overcoming structural issues of racism and poverty through hard work and self-sacrifice. Further, Black women are expected to be the pillars of the Black community. There is growing evidence, however, that this burden of strength harms Black women’s mental, emotional, and physical health.

My research suggests that the “Strong Black Woman” stereotype is a cultural ideal and psychological coping mechanism. Black women are required to respond to life’s hardships by portraying strength and concealing trauma. My conversations with Black college women highlight that even as they were praised for taking care of siblings, helping around the house, and excelling academically, their emotional displays of vulnerability, anger, and sadness were often met with resistance from family members. A recurring theme among the young women was that they had “never seen their mothers cry,” even as they extolled praise for how their mothers balanced multiple jobs, took care of grandparents, volunteered at church every Sunday, and made home-cooked meals throughout the week.

A Silent Mental Health Crisis

For context, consider the following:

Black women have lower-income jobs, more caregiver strain, less access to health care, higher exposure to traumatic events, and greater physical health problems than White women – all of which are associated with the onset and intensification of mental illness and psychological distress.

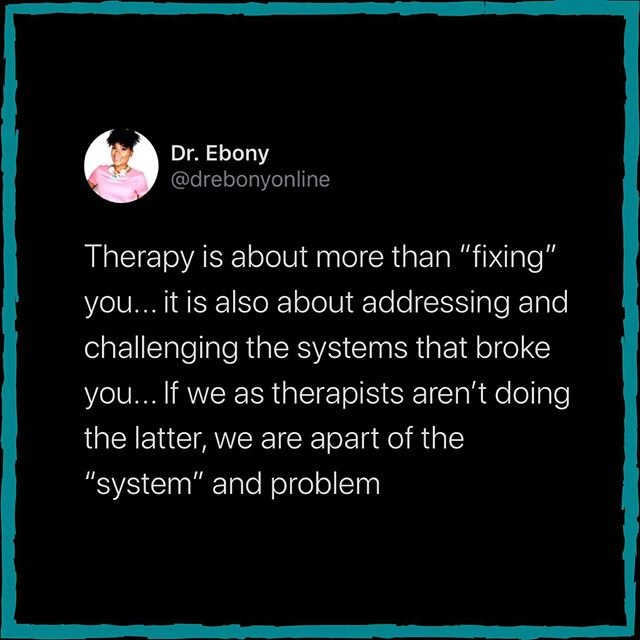

Black women’s mental illnesses often go undiagnosed due to issues of stigmatization and access to care. Black women often avoid seeking treatment for mental health concerns for fear of being called “crazy” or because of challenges seeking out and paying for mental health care.

Source: Scholar.org